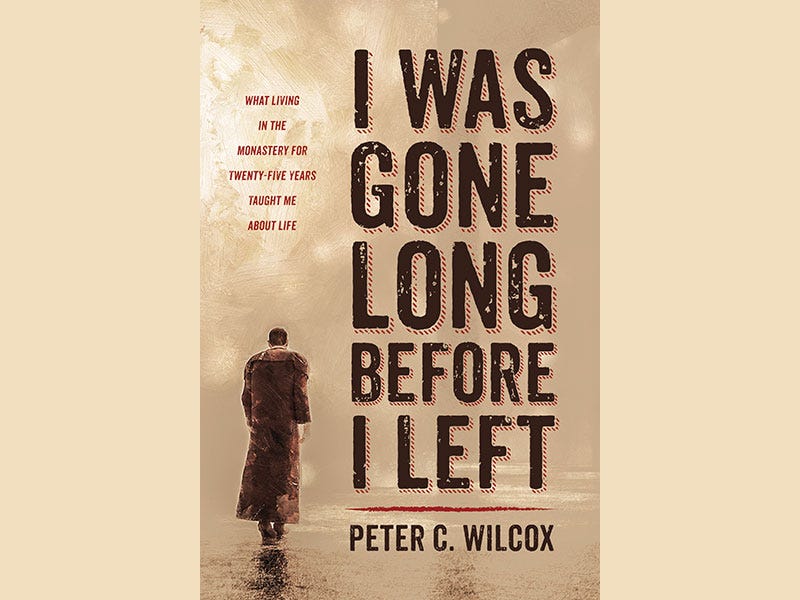

Book Review: "I Was Gone Before I Left."

I am not Roman Catholic. I know very little about monastic life, beyond reading the works of a select few medieval saints during my time attending a Protestant seminary. Yet when I read a brief summary of Peter Wilcox’s book: I Was Gone Before I Left: What Living in the Monastery for Twenty-Five Years Taught Me about Life, I knew that I needed to read it, in light of my own experience leaving a toxic institution.

Wilcox details his intense decades long struggle to leave the monastic life, although he knew during the initial stages of his training and studies that leaving would perhaps be in his best interest. Yet his leaving was impeded by many predominantly internal obstacles. Wilcox feared leaving the monastic life for numerous reasons: he worried that he would be a failure and a disappointment to those he loved, he was petrified that he would be letting God down, and especially, as the decades progressed, he was unsure of how he would survive in the outside world. After all, he had been training to be a priest since he was 15 years old. His days were heavily regulated and regimented. Most of his academic training had to do with theology. For a good chunk of his life the monastic life was all that he had ever known.

But living in the monastery was making him miserable. He battled with depression. Monastic life pre-Vatican II was also ruled by traditions that had become sacred not because they were truly “holy” or because the traditions were the best way to organize communal life but because they had been practiced for centuries. These traditions had, because of time and repetition, become an integral part of monastic life. It was how things were done and there was hesitancy to change. One tradition that Wilcox described stood out. It was called “the discipline.” On Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, each novice would whip themselves on the butt for three minutes while the novice master recited a “penitential psalm.” The purpose of this activity was to remind the novices about the suffering of Christ and to emphasize the weakness of human nature. He only briefly describes the tradition, which has since been discontinued, but the description helps readers understand a little bit about the type of atmosphere that prevailed within pre-Vatican II monastic life.

Wilcox also found living in community with the same people 24/7 while being largely isolated from the outside world to be extremely difficult. He would pray and spend time with the same group of people hour after hour and day after day and yet developing close friendships was discouraged. It was instilled since seminary, that “particular friendships” were to be avoided. Wilcox explains, “There was a great fear of guys who might be gay and so the way it was dealt with was to make us all afraid of particular friendships” (75).

And yet, even after changes in monastic life were ordered and began to be implemented in the wake of Vatican II, Wilcox continued to grapple with depression and a desire to leave the monastic life. He met with spiritual directors and psychiatrists, and took medication and yet the depression would not lift. He was suffering but he assumed that the problem was himself. If he could only be a more faithful priest, things would improve. If he could only surrender his unhappiness to God and trust God, he would be able to bear his cross and continue in monastic life. He desperately wanted to avoid disappointing other people and God. He was also scared. Leaving the monastery would mean plunging into the great unknown. He was not simply leaving a job but the only way of life he had known since he was 15.

Wilcox eventually does leave, although the institution made leaving difficult by forcing him to undergo a process that was grueling and onerous. Wilcox, understandably, finds this process to be incredibly unfair, especially in light of the Church’s lax treatment of pedophile priests. Yet despite all his fears, Wilcox builds a life filled with both triumphs and tragedies, outside of the monastery.

One of this book’s strengths is its accessibility. I know very little about monastic life yet I was still able to enjoy the book. Wilcox takes time to explain some of the basics of monastic life and he goes into details about his depression and his anguish over deciding whether to stay or leave. In fact, while in general I appreciated his attention to detail, there were a few occasions where readers would have benefited from less detail. For instance, I found the last chapter” “Finding My Way Home” to be very informative and Wilcox does a good job of wrapping up the themes he discusses throughout the book regarding what he learned during his years of depression and discernment. However, it would have been beneficial to split the chapter in two. The amount of detail and the scope of this chapter was a bit overwhelming.

I recommend this book to those who are in the midst of making difficult choices regarding their vocation and those debating whether or not to leave institutions that they have dedicated years of their life to. I gravitated toward this book because I have been floundering in my attempts to build a life outside of academia. I spent years and incurred massive amount of debt in academia, only to be essentially forced out. Reading about Wilcox’s journey has helped me process my own experience.

I am a member of Speakeasy. I received a free eBook copy of this book in exchange for my candid review.